The story of a bodyguard accused of murdering his Empress and employer, Dishonored is an anomaly in this day and age, both for its content and that it exists at all. This late in a console cycle, publishers as big as Bethesda Softworks are loathe to release entirely new IPs to the point that it almost seems as though it’s illegal to release a AAA game without a big-name license, a year, or a number attached to it. Yet as new and unique as it is to the video game industry at this point in time, I find my mind keeps slipping back to other games as I consider its merits.

The story of a bodyguard accused of murdering his Empress and employer, Dishonored is an anomaly in this day and age, both for its content and that it exists at all. This late in a console cycle, publishers as big as Bethesda Softworks are loathe to release entirely new IPs to the point that it almost seems as though it’s illegal to release a AAA game without a big-name license, a year, or a number attached to it. Yet as new and unique as it is to the video game industry at this point in time, I find my mind keeps slipping back to other games as I consider its merits.

What do Street Fighter, Grand Theft Auto, and Assassin’s Creed have in common? Without a doubt, they’re all iconic video game series. Though separated by console generations, they’ve come to represent some of the best of what video games have to offer in their own ways. Any writer seeking to pen a list of the greatest games of all time would be terribly remiss if they were to exclude any of these series entirely.

However, those three series are notable for another reason: Their first entries were lackluster, and with the possible exception of Assassin’s Creed, none of their initial offerings were any good. In all three cases, the concept was solid, but the developers were missing a crucial element that required more time or detail to truly craft a classic. Street Fighter needed precise controls, Assassin’s Creed needed more content, and Grand Theft Auto needed, well, another dimension. The potential was there, and the foundation was laid, but none of these games have stood the test of time.

Dear reader, you might be wondering what this has to do with Dishonored. The more astute readers can probably guess that I’m about to pay Dishonored and its developer, Arkane Studios, a well-meaning yet still backhanded compliment. Dishonored strikes so many of the right chords, but, in the process, it also hits many bum notes.

One of Dishonored’s key features is the freedom a player has throughout the game. Certainly a player can choose to approach Dishonored like every other first-person shooter or Western RPG on the market and blast their way through everything, but they’ll experience a much different game and, more importantly, an entirely different final act. Alternatively, the player can use subterfuge and stealth to progress through the game, and with enough dedication, patience, and saved games, it’s entirely possible to complete the game without killing anyone or alerting a single hostile to your presence.

All of this is interesting and, to my knowledge, completely unique for any game, much less a first-person shooter, a genre known for its high kill count and lack of subtlety. However, ignoring the caveat that this is only possible through the magic of stopping time and instant sleep darts, Dishonored’s stealth system is incredibly unpolished and inconsistent. For a game trying to be this serious, the game asks for too much suspension of disbelief. The player is expected to believe that leaning far around a corner or being obscured at the torso and below by a bed of flowers makes one invisible to guards. The boundary between visible and invisible really isn’t made clear throughout the game, but the player can mostly intuit its location through trial and error. Regardless, rest assured that it will come up as an annoyance at one point or another.

By itself, this would be excusable as necessary basic game mechanics. Invisible leaning isn’t any less plausible than leaning against a corner and getting a magical view around it ala Metal Gear Solid. Both games use unrealistic game mechanics to improve the quality of the game’s experience. Where Dishonored’s stealth system truly falls short is its enemy AI.

Enemies in Dishonored frequently patrol and have conversations. When the player breaks out of their prison cell at the beginning of the game, there are three guards yapping away about a card game they played the night before. Two of them walk off to patrol, and the other remains, guarding the cell block as easy pickings for the player. When the player takes out this guard, so long as they do so out of sight of the enemy, neither of the other two guards notices in the slightest that the first guard has mysteriously vanished. Jokes about how much money the other guards must owe the first guard aside, this same situation happens over and over again for the rest of the game and is as puzzling the hundredth time it happens as it is the first. There is no place for AI like this in a game that expects its player to take its characters seriously.

Corvo, the game’s protagonist, can knock out guards while they’re talking with another guard without alerting him. He can choke guards out while they’re in plain view of another guard without alerting this apparently nearsighted fellow. He can create a pile of unconscious guards without worrying that anyone will wake them up, and if he waits long enough, they’ll simply vanish from the room as if they never existed in the first place. All of this occurs without incident or alert in the game. Some of these aspects of Dishonored can be justified by genre convention but together make for a sloppy stealth game, especially when player-guard interactions comprise the majority of the gameplay.

All that said, the gameplay itself is refreshing and original. It’s reminiscent of the old Thief games, but the vast array of powers and tools that Corvo has to work with make Dishonored almost feel like a superhero stealth game. To take out an enemy, Corvo can use grenades, pistols, teleportation, or even time-stopping among several other options, and the majority of them are effective and fun in different circumstances. In the case of Dishonored’s Dark Vision power, similar to Arkham Asylum’s Detective Mode, it was almost too useful for stealth: I found myself playing far too much of the game in sepia.

The controls for sneaking up on an enemy and choking them are often finicky but mostly workable. I had a few unnecessary confrontations with an enemy solely because I needed to get into the right angle to choke him out and the icon wouldn’t pop up. If Corvo is a master assassin-bodyguard, he should be able to choke out a guard from a slightly diagonal position.

To Arkane’s credit, there were a number of times where I waited to choke a guard out just to hear a non-essential conversation simply because it was entertaining. The amount of peripheral content present in Dishonored is admirable at times and disappointing in others. Books and essays abound and contain pages and pages of reading material for a player to enjoy. Players will stumble upon many non-player characters having conversations concerning the events of the game. Those hoping for a world rich with expansion and detail will not be disappointed by the literature and dialogue.

Unfortunately, Dishonored does a better job of telling than showing. As the game progresses, players hear so much about the empire of Dishonored, yet everything and everyone looks mostly the same, and most areas are sparsely populated, even for a town suffering from a plague. When not in a scripted event, players will hear the same guards repeat the same mumblings over and over. The mystery of whale oil and its industrial revolution is frequently alluded to, but nothing ever comes of it outside being a plot device. The same is true of the source of Corvo’s powers, the mystical Outsider. He at least appears throughout Dishonored, but his only real purpose in the plot is to provide Corvo with supernatural abilities.

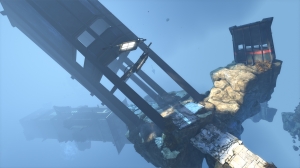

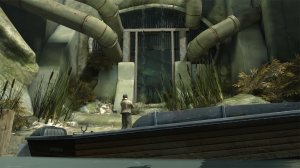

Graphically, the game won’t blow players away, but the art direction is satisfying and inspired. The PS3 version suffers from pop-in and many framerate problems in open areas. At one point, an NPC’s pipe started puffing out white blocks instead of smoke in my playthrough. If graphical difficulties such as this are a deal-breaker, avoid Dishonored on the PS3 entirely. Dishonored’s still-image quality is acceptable and sometimes brilliant.

Overall, Dishonored is a great start for a new IP. It learned from the few predecessors it has and made some missteps, but it’s a solid first outing with much to improve upon. Its core story is short, and its gameplay is repetitive, but there’s enough side material to be worth the price of admission. Those who enjoy steampunk-like aesthetics and value side-missions and lore should give Dishonored a try. Still, it’s not for everyone, and I’d advise players on the fence to skip it entirely, especially if they value gameplay, realism, or immersion above all else.

Gameplay

Graphics

Sound

Overall

Screenshots: